The Côte d’Or is a ridge of limestone in Burgundy, divided into the Côte de Nuits in the north and the Côte de Beaune in the south. It’s where the most famous red burgundies come from, with the famousest (and most expensive) coming from the Côte de Nuits. Here is a typical description of the difference between the two:

The top reds from the Côte de Nuits . . . often have greater intensity and a firmer structure than red wines from the Côte de Beaune . . . . By contrast, the top Côte de Beaune reds are frequently softer and sometimes more lush. In general, reds from all over the Côte d’Or are prized for their soaring, earthy flavors, often laced with minerals, exotic spices, licorice, or truffles.

—Karen MacNeil, The Wine Bible

In the last five years I have written 1030 tasting notes on CellarTracker, 41 on red wines from the Côte de Beaune and 34 on red wines from the Côte de Nuits (as of this writing; there will probably be more by the time this post is published). So I thought I’d do a text analysis to see if my notes reflect the difference described above. I used this online utility to create a word frequency list for each set of tasting notes. From that I created a list of descriptors. This included most words that refer to the aroma, flavor, or position on the palate. Some words were problematic: for example, the word “tannin” might be modified by “strong” or “weak,” but that information is lost in the frequency count. So I eliminated words related to strength of aroma, tannin, acid, fruit, or finish. It will take a later analysis to detect differences there. I also consolidated some terms—for example forest floor, stems, stemmy, heath, brambles, bracken, leaves, undergrowth—where I thought the distinction was likely to be noise.

Finally, I computed a CDB index for each descriptor: the frequency of a descriptor per tasting note for Côte de Beaune divided by the sum of the frequencies for Côte de Beaune and Côte de Nuits. Descriptors in the first section in the table below, with CDB index less than a third, are more than twice as likely to occur in a Côte de Nuits tasting note than in a Côte de Beaune, and it’s the other way around for descriptors in the third section. The descriptors in the middle section apply pretty well equally to all wines in the Côte d’Or.

So, to take a bit of poetic license with the table, red wines from the Côte d’Or in general are complex, with aromas of berry, violet, smoke, and undergrowth, and a nice spread of fruit on the palate with a focused core and crackling acids (well, “spread” and “focused core” are contradictory, so really it’s either/or there). Red wines from the Côte de Nuits are austere, elegant, and balanced, with shy flavors of strawberry, raspberry, blackcurrant, black cherry, earth, mocha, and thyme, whereas red wines from the Côte de Beaune are rich and soft with penetrating jammy fruit and crusty aromas of mushroom, leather, and sweet spice.

How much of this do I believe? Well, taking the flavor descriptors with a grain of salt, I think my tasting notes bear out the distinction noted by Karen MacNeil between the firm structure of Côte de Nuits and the soft lushness of Côte de Beaune. Beyond that, there is a savory/sweet dichotomy to the spices, perhaps some greater complexity in Côte de Nuits, perhaps some greater fruit concentration in Côte de Beaune. I suppose the next step is to do a blind tasting to see if these distinctions correctly guide identification.

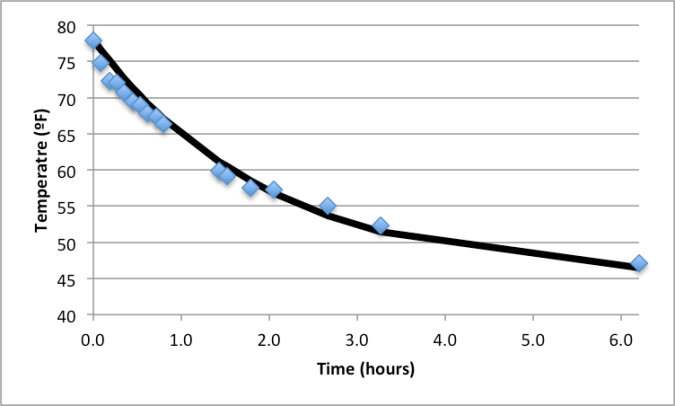

This was my first breathing experiment using the Coravin, on May 4, 2017. The methodology is the same as before, except that it uses one bottle instead of two. I poured half the bottle into a decanter 6 hours in advance using the Coravin, and left the other half corked under its blanket of argon. I used a

This was my first breathing experiment using the Coravin, on May 4, 2017. The methodology is the same as before, except that it uses one bottle instead of two. I poured half the bottle into a decanter 6 hours in advance using the Coravin, and left the other half corked under its blanket of argon. I used a